[ad_1]

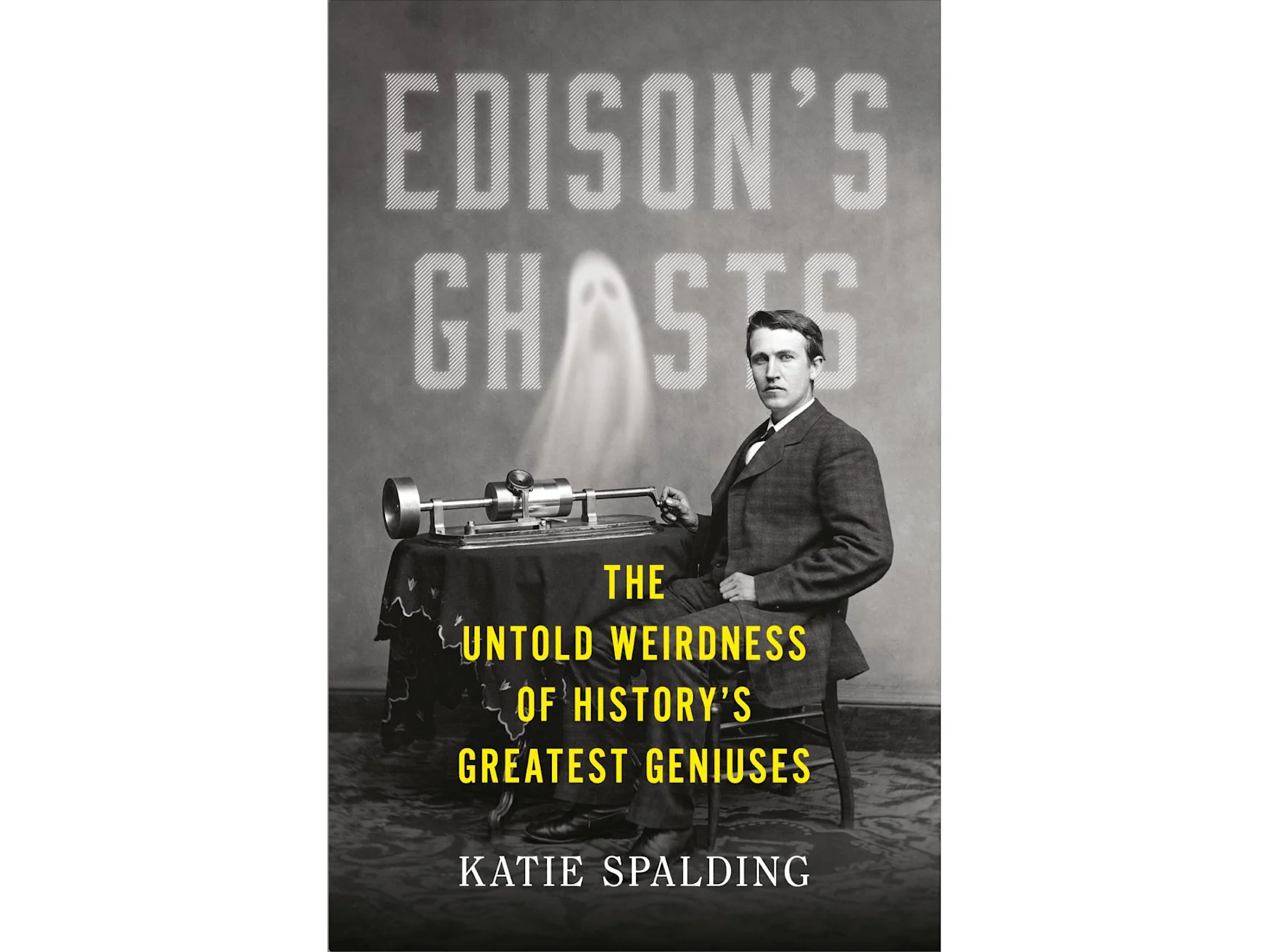

Some of us do our best thinking in the shower, others do it while on the toilet. Renee Descartes, he pondered most deeply while ensconced in a baker’s oven. The man simply needed to be convinced of the oven’s existence before climbing in. Such are the quirks of the most monumental minds humanity has to offer. In the hilarious and enthralling new book, Edison’s Ghosts: The Untold Weirdness of History’s Greatest Geniuses, Dr. Katie Spalding explores the illogical, unnerving, and sometimes downright strange behaviors of luminaries like Thomas “Spirit Phone” Edison, Isaac “Sun Blind” Newton, and Nicola “I fell in love with a pigeon” Tesla.

Little Brown and Company

Excerpted from Edison’s Ghosts: The Untold Weirdness of History’s Greatest Geniuses by Dr. Katie Spalding. Published by Little, Brown and Company. Copyright © 2023 by Katie Spalding. All rights reserved.

When René Descartes Got Baked

René Descartes, like Pythagoras before him and Einstein after, occupies that special place in our collective consciousness where his work has become … well, essentially a short-hand for genius-level intellect. Think about it – in any cartoon or sitcom where one character is (or, through logically-spurious means, suddenly becomes) a brainiac, there are three things they’re narratively bound to say: ‘the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides’ – that’s Pythagoras; ‘E = mc2’ – thank you, Einstein; and finally, ‘cogito ergo sum’. And that is Descartes.

Specifically, it’s old Descartes – Descartes after he had figured his shit out. But while his later writings undeniably played a huge and important role in setting up how we approach the world today – he’s actually one of the main figures who brought us the concept of the scientific method – Descartes’s early years leaned a little more on the silly and gullible than the master of scepticism he’s come to be known as.

Descartes was born in 1596, which places him firmly in that period where science and philosophy and magic were all pretty much the same thing. He’s probably best known as a philosopher these days, but that’s likely because a lot of his developments in mathematics have become so incredibly fundamental that we kind of forget they had to be invented by anybody at all. And I know I’m saying that with ten years of mathematical training behind me and a PhD on the shelf, but even if you haven’t set foot in a maths class since school, you’ll be familiar with something that Descartes invented, because he was the guy who came up with graphs. That’s actually why the points in a graph are given by Cartesian coordinates – it’s from the Latin form of his name, Renatus Cartesius.

And while maths, despite what everyone keeps telling me, can be sexy, ‘cogito ergo sum’ really does have a nice ring to it, doesn’t it? ‘I think, therefore I am.’ It doesn’t sound like a huge philosophical leap – in fact, it kind of sounds like tautological nonsense – but it’s actually one of the most important conclusions ever reached in Western thought.

See, before Descartes, philosophy didn’t exactly have the sort of wishy-washy, pie-in-the-sky reputation it enjoys today. The dominant school of thought was Scholasticism, which was basically like debate club mixed with year nine science. Sounds fair enough, but in practice – and especially when combined with the strong religious atmosphere and general lack of science up till that point – it was basically a long period of everybody riffing on Plato and Aristotle and trying to make their Ancient Greek teachings match up with the Bible. This was, needless to say, not always easy, and led to rather a lot of navel gazing over questions like ‘Do demons get jealous?’ and ‘Do angels take up physical space?’

Descartes’s approach was radically different. He didn’t see the point in answering questions like how many angels can dance on the head of a pin until he’d been properly convinced of the existence of angels. And dancing. And pins.

Now, of course, this is the point when non-philosophers throw up their hands in despair and say something along the lines of ‘Of course pins exist, you idiot, I have some upstairs keeping my posters up! Jesus, René, are we really paying a fortune in university fees just so you can sit around and doubt the existence of stationery?’

But to that, Descartes would reply: are you sure? I mean, we’ve all had dreams before that are so convincing that we wake up thinking we really did adopt a baby elephant after our teeth all fell out. How do I know I’m not dreaming now? How do I know this isn’t a The Matrix-type situation, and what you think are pins are just a trick being played on us by Agent Smith?

In fact, when you get right down to it, Descartes would say, how can we be sure anything exists? I might not even exist! I might be a brain in a vat, being cleverly stimulated in such a way as to induce a vast hallucination! And yes, sure, I agree that sounds unlikely, but it’s not impossible – the point is, we simply can’t know.

The only thing I can be sure of, Descartes would continue – despite everyone by this point rolling their eyes and muttering things like ‘see what you started, Bill’ – is that I exist. And I can be sure of that, because I’m thinking these thoughts about what exists. I may just be a brain in a vat, being fed lies about the reality that surrounds me, but ‘I’, ‘me’, my sense of self and consciousness – that definitely exists. To summarise: I think – therefore I am.

It was a hell of a breakthrough – he’d basically Jenga’d the entire prevailing worldview into obsolescence. And it’s the kind of idea that could really only have come from someone like Descartes: a weirdo celebrity heretic pseudo-refugee who had a weakness for cross-eyed women, weed and conspiracy theories.

Descartes was, as his name suggests, French by birth, hailing from a small town vaguely west of the centre of the country. If you look it up on a map, you’ll see it’s actually called Descartes, but it’s not some uncanny coincidence – the town was renamed in 1967 after its most famous resident.

Which is kind of odd, because it’s not like Descartes spent all that much time there. He went to school in La Flèche, more than 100km away, where even at the tender age of ten he was displaying the sort of behaviour that would make him perfectly suited to a life of philosophy, sleeping in until lunch every day and only attending lectures when he felt like it. This can’t have made him all that popular with the other kids, who were all expected to get up before 5am, but that’s why you choose a school whose rector is a close family friend, I suppose, and, in any case, by the time the young René turned up they were probably all too tired to do much about it.

After finishing high school, he spent a couple of years at uni studying law, as per his father’s wishes – his dad came from a less well-to-do branch of the Descartes family tree, and probably would have wanted Descartes to keep up appearances for the sake of holding on to posh perks like not paying taxes. It must have pained him, therefore, when after graduating with a Licence in both church and civil law, Descartes immediately gave it all up and went on an extended gap year. ‘As soon as my age permitted me to pass from under the control of my instructors, I entirely abandoned the study of letters, and resolved no longer to seek any other science than the knowledge of myself, or of the great book of the world,’ he would later write, like some kind of nineteen-year-old Eat Pray Love devotee.

‘I spent the remainder of my youth in travelling, in visiting courts and armies, in holding intercourse with men of different dispositions and ranks, [and] in collecting varied experience,’ he continued, in his philosophical treatise-slash-autobiography Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One’s Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences, which for obvious time-saving reasons is usually referred to as Discourse on the Method. Andlike so many philosophy students throughout history, there was one place he found in his travels that caught Descartes’s heart and imagination more than anywhere else: Amsterdam.

Now, it is of course true that places can change a lot over the course of 400 years – at this point in history, France was being ruled by a nine-year-old autocrat and his mum, Germany didn’t exist, and England was a few years short of becoming a Republic. So you might think, sure, these days Amsterdam has a bit of a reputation, but back in Descartes’s time, it was probably a hub of quiet intellectualism and sombre, clean living.

Nope! Dynasties may rise and fall, empires spread and eventually fracture, but apparently, Amsterdam has always been Amsterdam. Descartes spent his first few years in the city living his absolute best life, studying engineering and maths under the direction of Simon Stevin – another guy you’ve never heard of who made a mathematical breakthrough you almost certainly use every single day of your life, since he invented the decimal point – and dressing like an emo and throwing himself into music. He joined the Dutch army for a bit, despite being by all accounts a tiny weedy bobble-headed French guy, and, yes, he almost certainly smoked a bunch of pot along the way.

And then, one November night in 1619, while on tour in Bavaria, Descartes had a Revelation. And he had it, according to his near-contemporary biographer Adrien Baillet, inside an oven.

‘He found himself in a place so remote from Communication, and so little frequented by people, whose Conversation might afford him any Diversion, that he even procured himself such a privacy, as the condition of his Ambulatory Life could permit him,’ Baillet writes.

‘Not … having by good luck any anxieties, nor passions, within, that were capable of disturbing him, he staid withal all the Day long in his stove, where he had leisure enough to entertain himself with his thoughts,’ he continues, as if that’s a normal thing to write and not an account of someone being so introverted that they secluded themselves miles away from anyone who knew them and then crawled into an oven for the day.

Modern biographers have suggested a few interpretations of what this oven might have been, and I’m sorry to report that, of course, it’s not as ridiculous as it first seems: in the seventeenth century, before we’d tamed electricity and gas mains and whatnot, a ‘stove’ or ‘oven’ was more like your modern-day airing cupboard than an Aga. Just bigger. And fancier. And all your towels are on fire. Look, the analogy isn’t perfect, but the point is that when Descartes said, in Discourse on the Method, that he had ‘spent all day entertaining his thoughts in an oven’, he wasn’t being completely absurd – just, you know, kind of weird.

Depending on where you fall on the scale between ‘Descartes was a stoner lol’ and ‘Descartes was a paragon of virtue, 10/10 no notes awesome dude’, what happened next was either the result of too much weed, too much oven, or too much being a fricking genius destined to reform all of Western philosophy. Either way, he had a pretty rough night, full of strange dreams and disturbing hallucinations* that even the loyal Baillet thought might be a sign he was going a little bonkers.

‘He acquaints us, That on the Tenth of November 1619, laying himself down Brim-full of Enthusiasm, and … having found that day the Foundations of the wonderful Science, he had Three dreams one presently after another; yet so extraordinary, as to make him fancy that they were sent him from above,’ writes Baillet, just in case you were wondering where on that scale Descartes would put himself. In fact, so sure was he of the divine nature of his dreams that, Baillet said, ‘a Man would have been apt to have believed that he had been a little Crack-brain’d, or that he might have drank a Cup too much that Evening before he went to Bed.

‘It was indeed, St. Martin’s Eve, and People used to make Merry that Night in the place where he was … but he assures us, that he had been very Sober all that Day, and that Evening too and that he had not touched a drop of Wine for Three Weeks together.’

Sure, René. Though honestly, the content of the dreams aren’t as noteworthy as the conclusions he drew from them – unless you think ‘walking through a storm to collect a melon from a guy’ is super weird, I guess. And goodness knows how he got from cantaloupe to conceptualism, but these three dreams are said to have given him the inspiration first for analytic geometry – that is, his maths stuff – and then the realisation that he could apply the same kind of logical rigour to philosophy. And I don’t want to minimise what Descartes achieved after this melon-based enlightenment – it takes guts to stand up in a world governed by strict ritual and belief and announce that not only is everyone around you an idiot, but also they probably don’t even exist, so there. But have you ever heard that saying about not being so open-minded that your brain falls out?

Well, 1619 was also the year that Descartes, writing under the pseudonym ‘Polybius Cosmopolitanus’ – Polybius being an ancient Greek historian, and Cosmopolitanus being Latin for ‘citizen of the world’ – released the Mathematical Thesaurus of Polybius Cosmopolitanus. It kind of sounds like a Terry Gilliam movie, but it was actually a proposal for a way to reform mathematics as a whole.

It doesn’t matter that you’ve never heard of it. It’s not as famous as the Discourse; in fact, it may not have ever even been completed. The important bit wasn’t what was contained inside the book, but who it was dedicated to: to ‘learned men throughout the world, and especially to the F.R.C. very famous in G[ermany].’

And who was this mysterious F.R.C? Descartes was specifically referencing the Frères de la Rose Croix. In English, they were known as the Brothers of the Rosy Cross – and, today, they’re called the Rosicrucians. So, you may have heard of the Rosicrucians, but it’s more likely you haven’t. Today, the term actually refers to two separate organisations, both of which claim to be the ‘real’ Rosicrucians and both of which denounce the other group as being a bunch of weirdos. They’re equally wrong on the first point, and equally right on the second: there’s no Rosicrucian group around today that is directly linked to the original group that Descartes was a fan of, and every iteration of the organisation is and always has been fucking bananas.

But people in search of a new outlook on the universe often don’t get to choose which batshit philosophy the world throws at them first, and Descartes had the peculiar fortune of going through his minor mental breakdown in early seventeenth-century Germany.

Between 1614 and 1616, three ‘manifestos’ were published in Germany. They were anonymous, recounting the tale of one Christian Rosenkreuz, a man who was born in 1378, travelled across the world, studied under Sufi mystics in the Middle East, came back to Europe to spread the knowledge he had gained in his travels, was rejected by Western scientists and philosophers, and so founded the Rosicrucian Order, a grand name for what was apparently a group of about eight nerdy virgins. All of this, the manifestos said, he accomplished by the age of about twenty-nine, after which he presumably just sat on his thumbs for a long old while since the next big thing he’s said to have done was die aged 106.

Now, some people have posited that everything you just read is false – a kind of early modern conspiracy theory. And yes, ‘Christian Rose-Cross’, as the name translates from German, is rather on the nose for the founder of a Christian sect, and, yes, it’s a bit farfetched for anybody to have lived for more than a century in the 1400s, and, yes, OK, so the last manifesto was almost certainly actually written by a German theologian named Johann Valentin Andreae, who was attempting to take the piss out of the whole thing and publicly renounced it when he realised people were taking him seriously – but that’s the thing: people did take it seriously. And one of the people who took it seriously seems to have been Descartes.

‘There is a single active power in things: love, charity, harmony,’ mused the philosopher most famous for radical doubt of everything that couldn’t be proved via logic alone. Not in any published work – these were the thoughts of Descartes the early-twenties guy just trying to figure his shit out, found years later in the journal he kept throughout his life.

Another: ‘The wind signifies spirit; movement with the passage of time signifies life; light signifies knowledge; heat signifies love; and instantaneous activity signifies creation. Every corporeal form acts through harmony. There are more wet things than dry things, and more cold things than hot, because if this were not so, the active elements would have won the battle too quickly and the world would not have lasted long.’

If that sounds, you know, completely ridiculous to you, that’s probably because we live in a post-Descartes world, and he didn’t. All this poor oven-baked idiot had at his disposal were a dream about melons, a steadfast conviction that he had been personally chosen by God to reform the entirety of Western thought up until that point, and some rumours about a weird sect of rosy German virgins who were devoted to doing just that.

You may have already guessed the next bit of the story: Descartes joins the Rosicrucians and embarks on some insane rituals and philosophies that we’ve never heard of today because it doesn’t fit in with our modern ideas of ‘genius’, right?

It’s actually way more stupid than that. In a series of events that, once again, really feels like it was ripped straight out of some cult comedy movie, Descartes tried to join the Rosicrucians, but kept running into the problem of them not, in fact, existing. So he couldn’t join the group, but what he could and did do was accidentally make everyone think he had joined, thus entirely screwing over his reputation as someone to take seriously.

Of course, in the grand scheme of things, this didn’t matter much, because to a lot of people he was dangerous enough even without all the conspiracy stuff: his insistence that truth was something for humans, not God, to judge, and the idea that authority should or even could be questioned, made him an enemy of most established Churches, so much so that he eventually published an extremely circular and nonsensical ‘proof’ of God’s existence to try to placate his attackers.

The irony was that Descartes knew God existed – otherwise who had told him to transform philosophy and mathematics via the medium of melons? And, ultimately, as hubristic as this claim was, Descartes did make good on it, publishing the end result of that night in the oven in the 1640s with a slew of philosophical and metaphysical treatises, which were hailed in his beloved Netherlands as ‘heretical’ and ‘contrary to orthodox theology’ and ‘get out of our goddamn town Descartes.’

Eventually, Descartes found refuge with Christina, Queen of Sweden, who was a fan of his ideas about science and love. She invited him to her court with the promises of setting up a new scientific academy and tutoring her personally. It seemed too good to be true. It was. In 1649, in the middle of winter, Descartes moved to Queen Christina’s cold, draughty Swedish castle and discovered that he couldn’t fucking stand his new boss or home. Worst of all for the philosopher who lived his entire life by the principle of never once waking up before noon, Christina declared that she could only be tutored at five in the morning, a demand that Descartes responded to as any night owl would: by saying ‘I would literally rather die’ and promptly proving his point by literally dying just a few months later. In his final act, the man famous for telling the world ‘I think, therefore I am’ had posed an equally unknowable philosophical conclusion: he would no longer think, and therefore he no longer existed.

Perhaps the final irony in the tale is that, as heretical as cogito ergo sum was considered at the time, with its previously unthinkably radical concept of doubting everything, even that which seems self-evident – modern philosophers have actually critiqued Descartes as not going far enough. Thinkers such as Kierkegaard have blasted Descartes for presupposing that ‘I’ exists at all, and Nietzsche for presupposing that ‘thinking’ exists.

I guess the moral of Descartes’s story, if there is one, is probably this: you can’t please all of the people all of the time – especially if they’re philosophers. So, honestly? Why not just smoke a bunch of weed and crawl into an oven?

* Some modern scientists have suggested that Descartes’s night in the oven may in fact be the earliest recorded experience of Exploding Head Syndrome, a sleep disorder you may well have had yourself once or twice. Despite the gnarly name, it doesn’t actually involve your head exploding – that would certainly have made Descartes’s future work more impressive – but it does cause you to hear loud bangs and crashes that aren’t really there, and sometimes see flashes of light as well, both of which Descartes recorded experiencing that night.

All products recommended by Engadget are selected by our editorial team, independent of our parent company. Some of our stories include affiliate links. If you buy something through one of these links, we may earn an affiliate commission. All prices are correct at the time of publishing.

[ad_2]

Source link